The experience of womanhood and perspectives on women have evolved across different historical periods and societies. However, the condition of being a woman and the significance of the female body have remained central issues for centuries. Regardless of whether one approves or disapproves, nearly everyone holds an opinion about women and assigns them a particular role, accompanied by specific expectations. This phenomenon is not exclusive to women; the positions attributed to them inevitably shape the roles and expectations imposed on men as well. In this paper, I will explore this issue through the lens of existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir’s insights on gender and, more fundamentally, womanhood.

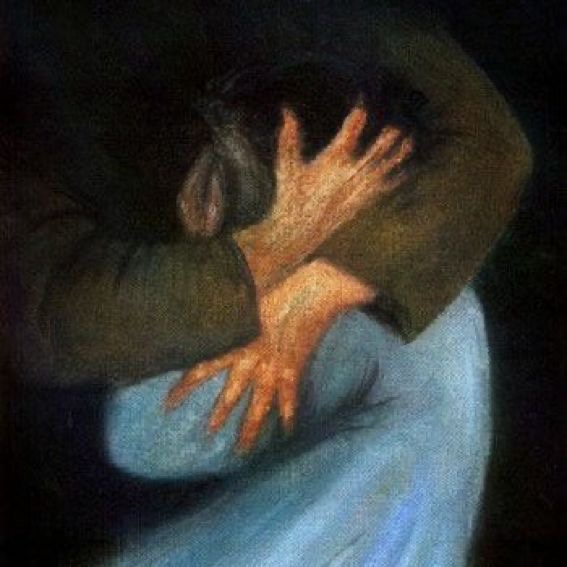

In The Second Sex (1949), Simone de Beauvoir underscores the asymmetry between genders as an existential rupture. She critiques the ways in which patriarchal society objectifies the female body (la chair), while defining the male body as an active, "living" entity (le corps). Beauvoir argues that men relegate women to the status of "the Other," a condition reinforced by patriarchal myths such as "Mother Nature." Consequently, while women should ideally exist as whole beings, embodying both "body-for-itself" and "body-for-others," they instead become entirely "being-for-others," resulting in a fractured existence.

The extreme objectification and passivization of the female body have further contributed to the illusion that the male body is purely a subject, seemingly unencumbered by the physical constraints of human existence. Beauvoir asserts that a woman raised in a patriarchal society is neither permitted to adopt an active stance toward the world nor encouraged to engage in activities that foster the realization of her individuality. As a result, she remains caught in a perpetual conflict between her own body, desires, individuality, and the demands imposed by society (Tiukalo, 2012).

Beauvoir, who posits that women are perceived as "the Other" in male-dominated societies, emphasizes that this status inherently objectifies them. To be persistently objectified is to be rendered available for use. Beauvoir (1949, p. 280) describes how, unlike men, women are conditioned into objectification from childhood:

A man’s life unfolds through a free engagement with the external world; he competes with other men both harmoniously and independently, evaluating girls. He climbs trees, engages in fights, and plays rough games—his body serves as a tool for conquering nature, a weapon for combat. He takes pride in his masculinity and his physical strength; through sports, games, fights, and trials of endurance, he experiences his power in a balanced manner. Concurrently, he learns harsh lessons: from an early age, he is taught to withstand pain, suppress tears, and endure physical hardships. He commits, invents, and dares. In contrast, women encounter an early and persistent conflict between their autonomous experience and their objectified self—the state of 'otherness.' They are treated like dolls, denied freedom. This creates a vicious cycle: the less they utilize their freedom to understand, explore, and engage with the world, the fewer internal resources they develop, and the less courage they possess to affirm themselves as subjects. If a girl were encouraged, she could exhibit the same enthusiasm, curiosity, initiative, and adaptability as a boy. This is only possible when she is raised in an environment that does not impose restrictive gender norms, allowing her to develop freely.

A woman, perceived as passive, obedient, and gentle, must exert extra effort to attain the autonomy readily afforded to men. Asserting herself, articulating her desires freely, and embodying her true self remain far more challenging for a woman than for a man. While each woman’s experiences are unique, the societal pressures, exclusion, and "otherness" that shape their realities are universal, though manifesting in different ways depending on individual circumstances. Beauvoir (1949) contends that a woman raised in such a society often remains unaware of her own desires.

Beauvoir also examines whether biological factors contribute to this societal positioning. She frequently highlights the asymmetry between male and female bodies, particularly regarding sexuality. She argues that men possess an inherent physical privilege, enabling them to engage with the world freely. Women, in contrast, navigate existence through a body subject to cyclical changes and biological limitations. Beauvoir suggests that a woman’s biological structure significantly influences her perception of and engagement with the world. The most fundamental example is childbirth, which inherently positions women in an objectified role. In other words, she contends that the passivity of the female body is not solely a societal construct but also has biological underpinnings.

Critics argue that Beauvoir devalues the female body by grounding her analysis in biological determinism (Doney, 2011). They claim that in critiquing the objectification of the female body, she paradoxically reinforces it. However, Beauvoir counters this critique by asserting that she merely presents a social and biological reality. She contends that while biological conditions exist, they need not result in objectification. Although a woman’s biological conditions may pose challenges to realizing her aspirations, Beauvoir argues that she must actively assert her living body and engage with the world in defiance of objectification.

Beauvoir does not merely lament the rigid dichotomy between the subjectivity of men and the objectification of women. She characterizes the division of bodily existence—where men are subjects and women are objects—as a form of mauvaise foi (bad faith) in Sartrean terms. This bad faith negates an individual’s fundamental freedom, stripping men of their objectivity and women of their subjectivity.

According to Beauvoir, a woman is a free human being entitled to assert the subjectivity of her body. She argues that all genders should have the autonomy to express their bodily existence on their own terms. The physical differences between men and women should not serve as justifications for hierarchical societal structures. A woman’s physical weakness does not render her inferior. In other words, biology does not define gender.

Biological differences are undeniably significant. Biology plays a crucial role in shaping the history of women and their societal positioning. However, it is insufficient to justify a gender hierarchy; it cannot explain why women are regarded as 'the Other' or why they should remain in a subordinate position indefinitely. (Beauvoir, 1945, pp. 32-33)

Beauvoir (1949) asserts that individuals should be capable of experiencing both subject and object positions and finding fulfilment in both. The fundamental issue is that men are excessively subjectified, while women are excessively objectified, making the subjugation of the female body inevitable. However, this does not mean that women are doomed to remain in this position. To accept such a fate would itself constitute an act of bad faith. Beauvoir insists that the path to genuine liberation lies in women’s struggle to assert themselves as free and autonomous individuals, reclaiming their role as subjects.

If every individual recognizes the freedom of others and grants them the simultaneous and mutual possibility of being both subject and object, this conflict can be overcome. However, in reality, friendship and generosity—virtues that enable the recognition of these free beings—are not easily achieved. These virtues represent humanity’s greatest accomplishment, through which individuals realize their true nature. (Beauvoir, 1945, p. 140)

References

Beauvoir, S. de (1949). The Second Sex. Vintage Books, New York. Doney, T. (2011).

Freedom and the Body: Sartre and Beauvoir on Embodied Consciousness. Tiukało, A. (2012).

The Notion of the Body and Sex in Simone de Beauvoir’s Philosophy. Human Movement, 13(1). doi:10.2478/v10038-012-0008-3